(Translation: Zelelaem Aberra Tesfa)

http://www.zelealemaberra.com/?page_id=388

Although sub-Saharan Africa receives $134bn each year in loans, foreign investment and development aid, $192bn leaves the region, leaving a $58bn shortfall. See @ http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/jul/15/aid-africa-west-looting-continent?CMP=fb_ot

Mark Anderson writes for the Guardian:

Western countries are using aid to Africa as a smokescreen to hide the “sustained looting” of the continent as it loses nearly $60bn a year through tax evasion, climate change mitigation, and the flight of profits earned by foreign multinational companies, a group of NGOs has claimed.

Although sub-Saharan Africa receives $134bn each year in loans, foreign investment and development aid, research released on Tuesday by a group of UK and Africa-based NGOs suggests that $192bn leaves the region, leaving a $58bn shortfall.

It says aid sent in the form of loans serves only to contribute to the continent’s debt crisis, and recommends that donors should use transparent contracts to ensure development assistance grants can be properly scrutinised by the recipient country’s parliament.

“The common understanding is that the UK ‘helps’ Africa through aid, but in reality this serves as a smokescreen for the billions taken out,” said Martin Drewry, director of Health Poverty Action, one of the NGOs behind the report. “Let’s use more accurate language. It’s sustained looting – the opposite of generous giving – and we should recognise that the City of London is at the heart of the global financial system that facilitates this.”

Research by Global Financial Integrity shows Africa’s illicit outflows were nearly 50% higher than the average for the global south from 2002-11.The UK-based NGO ActionAid issued a report last year (pdf) that claimed half of large corporate investment in the global south transited through a tax haven.

Supporting regulatory reforms would empower African governments “to control the operations of investing foreign companies”, the report says, adding: “Countries must support efforts under way in the United Nations to draw up a binding international agreement on transnational corporations to protect human rights.”

But NGOs must also change, according to Drewry: “We need to move beyond our focus on aid levels and communicate the bigger truth – exposing the real relationship between rich and poor, and holding leaders to account.”

The report was authored by 13 UK and Africa-based NGOs, including:Health Poverty Action, Jubilee Debt Campaign, World Development Movement, African Forum and Network on Debt and Development,Friends of the Earth Africa, Tax Justice Network, People’s Health Movement Kenya, Zimbabwe and UK, War on Want, Community Working Group on Health Zimbabwe, Medact, Healthworkers4All, Friends of the Earth South Africa, JA!Justiça Ambiental/Friends of the Earth Mozambique.

Sarah-Jayne Clifton, director of Jubilee Debt Campaign, said: “Tackling inequality between Africa and the rest of the world means tackling the root causes of its debt dependency, its loss of government revenue by tax dodging, and the other ways the continent is being plundered. Here in the UK we can start with our role as a major global financial centre and network of tax havens, complicit in siphoning money out of Africa.”

A UK government spokesman said: “The UK put tax and transparency at the heart of our G8 presidency last year and we are actively working with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to ensure companies are paying the tax they should and helping developing countries collect the tax they are owed.” Read @http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/jul/15/aid-africa-west-looting-continent?CMP=fb_ot

BY HENRY FARRELL

(Washington Post, 26th June 2014), There’s a lot of recent scholarship suggesting that non-democratic regimes grow faster than democratic regimes. This has led some people not only to admire the Chinese model of growth focused authoritarianism, but to suggest that it may be a better economic model for developing countries than democracy. However, this research tends to assume that both democracies and non-democracies are telling the truth about their growth rates, when they report them to multilateral organizations such as the World Bank. Is this assumption safe? The answer is no, according to aforthcoming article (temporarily ungated) by Christopher S. P. Magee and John A. Doces in International Studies Quarterly.

The problem that Magee and Doces tackle is that it’s hard to figure out when regimes are being honest or dishonest about their rates of economic growth, since it’s the regimes themselves that are compiling the statistics. It’s hard to measure how honest or dishonest they are, if all you have to go on are their own numbers. This means that researchers need to find some kind of independent indicator of economic growth, which governments will either be less inclined or unable to manipulate. Magee and Doces argue that one such indicator is satellite images of nighttime lights. As the economy grows, you may expect to see more lights at night (e.g. as cities expand etc). And indeed, research suggests that there’s a very strong correlation between economic growth and nighttime lights, meaning that the latter is a good indicator of the former. Furthermore, it’s an indicator that is unlikely to be manipulated by governments.

Magee and Doces look at the relationship between reported growth and nights at light and find a very clear pattern. The graph below shows this relationship for different countries – autocracies are the big red dots. Most of the dots are above the regression line, which means that most autocracies report higher growth levels to the World Bank than you’d expect given the intensity of lights at night. This suggests that they’re exaggerating their growth numbers.

The two countries with the biggest difference between their reported growth and their actual growth (as best as you can tell from the intensity of nighttime lights) are China (although the discrepancy was considerably larger in the mid-1990s than now) and Myanmar. More broadly:

If democracies report their GDP growth rates truthfully, then dictatorships overstate their yearly growth rate by about 1.5 percentage points on average. If democracies also overstate their true growth rates, then dictatorships exaggerate their yearly growth statistics by about 1.5 percentage points more than do democracies.

The authors conclude:

the existing literature on economic growth overestimates the impact of dictatorships because it relies on statistics that are reported to international organizations, and as we show, dictatorships tend to exaggerate their growth. Accounting for the fact that authoritarian regimes overstate growth slightly diminishes the effect of these regimes on long-run economic growth. In light of this point, much of the evidence showing growth benefits associated with authoritarian regimes is less compelling and the case for democracy looks better than before. See more @ http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2014/06/26/dictators-lie-about-economic-growth?Post+generic=%3Ftid%3Dsm_twitter_washingtonpost

Related Article:

What if everything we know about poor countries’ economies is totally wrong?

Read @ http://www.vox.com/2014/7/10/5885145/what-if-everything-we-know-about-poor-countries-economies-is-totally?utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook&utm_name=share-button&utm_campaign=vox&utm_content=article-share-top

(OPride) – Over the last decade, Ethiopia has been hailed as the fastest growing non-oil economies in Africa, maintaining a double-digit annual economic growth rate. The Ethiopian government says the country will join the middle-income bracketby 2025.

Despite this, however, as indicated by a recent Oxford University report, some 90 percent of Ethiopians still live in poverty, second only after Niger from 104 countries measured by the Oxford Multidimensional Poverty Index. The most recent data shows an estimated 71.1 percent of Ethiopia’s population lives in severe poverty.

This is baffling: how can such conflicting claims be made about the same country? The main source of this inconsistent story is the existence of crony businesses and the government’s inflated growth figures. While several multinational corporations are now eyeing Ethiopia’s cheap labor market, two main crony conglomerates dominate the country’s economy.

Meet EFFORT, TPLF’s business empire

The seeds of Ethiopia’s economic mismanagement were sown at the very outset. We are familiar with rich people organizing themselves, entering politics and protecting their group interests. But something that defies our knowledge of interactions between politics and business happened in 1991 when the current regime took power.

Ethiopia’s ruling party, the EPRDF, came to power by ousting the communist regime in a dramatic coup. A handful of extremely poor people organized themselves exceptionally well that they quickly took control of the country’s entire political and military machinery.

In a way, this is analogous to a gang of thieves becoming brutally efficient at organizing themselves to the extent of forming a government. Once in power, the ruling Tigrean elites expropriated properties from other businesses, looted national assets and began creating wealth exclusively for themselves.

This plan first manifested itself in the form of party affiliated business conglomerate known as the Endowment Fund for Rehabilitation of Tigray (EFFORT). EFFORT has its origin in the relief and rehabilitation arm of the Tigrean People Liberation Front (TPLF) and the country’s infamous 1984 famine.

As reported by BBC’s Martin Plaut and others, the TPLF financed its guerilla warfare against the Dergue in part by converting aid money into weapons and cash. That was not all. On their way to Addis Ababa from their bases in Tigray, the TPLF confiscated any liquid or easily moveable assetsthey could lay their hands on. For instance, a substantial amount of cash was amassed by breaking into safe deposits of banks all over Ethiopia. Those funds were kept in EFFORT’s bank accounts. TPLF leaders vowed to use the loot to rehabilitate and reconstruct Tigray, which they insisted was disproportionately affected by the struggle to “free Ethiopia.”

Intoxicated by its military victory, the TPLF then turned to building a business empire. EFFORT epitomizes that unholy marriage between business and politics in a way not seen before in Ethiopian history. According to a research by Sarah Vaughan and Mesfin Gebremichael, EFFORT, which is led by senior TPLF officials, currently owns 16 companies across various sectors of the economy.

This figure grossly understates the number of EPRDF affiliated companies. For example, the above list does not include the real money-spinners that EFFORT owns: Wegagen Bank, Africa Insurance, Mega Publishing, Walta Information Center and the Fana Broadcasting Corporate. The number of companies under EFFORT is estimated to be more than 66 business entities. Suffice to say, EFFORT controls the commanding heights of the Ethiopian economy.

While it is no secret that EFFORT is owned by and run exclusively to benefit ethnic Tigrean elites, it is a misnomer to still retain the phrase “rehabilitation of Tigray.” Perhaps it should instead be renamed as the Endowment Fund for Rendering Tigrean Supremacy (EFFORTS).

MIDROC Ethiopia, EPRDF’s joker card

In Ethiopia’s weak domestic private environment, EFFORT is an exception to the rule. Similarly, while Ethiopia suffers from lack of foreign direct investment, MIDROC Ethiopia enjoys unparalleled access to Ethiopia’s key economic sectors. Owned by Ethiopian-born Saudi business tycoon, Sheik Mohammed Al Amoudi, MIDROC has been used by the EPRDF as a joker card in a mutually advantageous ways. The Sheik was given a privilege no less than the status of a domestic private investor but the EPRDF can also count it as a foreign investor. For instance, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development reported that about 60 per cent of the overall FDI approved in Ethiopia was related to MIDROC.

MIDROC stands for Mohammed International DevelopmentResearch and Organization Companies. Despite reference to development and research in its name, however, there is no real relationship between what the crony business says and what it actually does. Ironically, as with EFFORT, MIDROC Ethiopia also owns 16 companies. But this too is a gross underestimation given the vast sphere of influence and wealth MIDROC commands in that country.

Like EFFORT, Al-Amoudi’s future was also sealed long before the TPLF took power. He literally entered Addis Ababa with the EPRDF army, fixing his eyes firmly on Oromia’s natural resources. Shortly after the TPLF took the capital, Al-Amoudi allegedly donated a huge sum of money to the Oromo People’s Democratic Organization.

Why the rush?

The calculative Sheik sensed an eminent threat to his business interests from the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), a groups that was also a partner in the transitional government at the time. In return for its “donation,” MIDROC acquired massive lands in Oromia – gold mines, extensive state farms and other agricultural lands. In a recent article entitled, “The man who stole the Nile,” journalist Frederick Kaufman aptly described Al Amoudi’s role in the ongoing land grab in Ethiopia as follows:

In this precarious world-historic moment, food has become the most valuable asset of them all — and a billionaire from Ethiopia named Mohammed Hussein Al Amoudi is getting his hands on as much of it as possible, flying it over the heads of his starving countrymen, and selling the treasure to Saudi Arabia. Last year, Al Amoudi, whom most Ethiopians call the Sheikh, exported a million tons of rice, about seventy pounds for every Saudi citizen. The scene of the great grain robbery was Gambella, a bog the size of Belgium in Ethiopia’s southwest whose rivers feed the Nile.

It is little wonder then that Al-Amoudi said, “I lost my right hand,” when Ethiopia’s strongman of two decades Meles Zenawi died in 2012. If EFFORT is a curse to the Ethiopian economy, MIRDOC is EPRDF’s poisoned drink given to the Ethiopian people.

Mutual Distrust

The marriage between politics and business has had damaging effects on the country’s economy. One of its most far-reaching consequences is the total breakdown of trust between the EPRDF and the Ethiopian people. In economic policy, trust between private investors and the government is paramount. The deficit of trust is one of the hallmarks of Ethiopia’s much-touted development.

After all youth unemployment hovers around 50 percent. Every year, hundreds of young Ethiopians risk their lives trying to reach Europe or the Middle East, often walking across the Sahara desert or paying smugglers to cross the Red Sea or Indian Ocean aboard crowded boats. The desperation is a result of the lack of confidence in the government’s ability to provide them with the kind of future they were promised.

Ironically, aside from their crony businesses, the EPRDF does not have any confidence in Ethiopian entrepreneurs either. It is this mutual distrust that culminated in the prevalence of an extremely hostile environment for domestic private investment.

This is not a speculative claim but a well-documented fact. The World Bank’s annual survey, which measures the ease with which private investors can do business, ranks Ethiopia near the bottom. In the 2014 survey, Ethiopia came in 166th out of 189 countries in terms of difficulties in starting new business or trading across borders. Moreover, year on year comparison shows that the investment climate in Ethiopia is actually getting worse, sliding down the ranking both in the ease of doing business and trading across borders.

Farms but no firms

The TPLF cronies do not engage in competitive business according to market rules but act as predators bent on killing existing and emerging businesses owned by non-Tigrean nationals. However, the ruling party, which largely maintains its grip on power using bilateral and multilateral aid, is required to report its economic progress to donors (the regime does not care about accountability to the people). In this regard, the lack of foreign direct investment (FDI) has been a thorn in the throat of the EPRDF. Donors have repeatedly questioned and pressured the EPRDF to attract more FDI. The inflow of FDI is often seen as a good indicator of the confidence in countries stability and sound governance. Despite widespread belief in the West, the EPRDF regime cannot deliver on these two fronts.

To cover up these blind spots, the regime has persuaded a handful of foreigners to invest in Ethiopia, but until recently few investors considered any serious manufacturing venture in the country. Besides, considered “cash cows” for the government, banks, the Ethiopian Airlines, telecommunication and energy sectors remain under exclusive monopoly of the state. They provide almost free service to the crony businesses. Any firm looking to invest in manufacturing and financial sectors have to overcome insurmountable bureaucratic red tape and other barriers.

One sector that stands as exception to this rule is agriculture. Since the 2008 financial crisis and the rise in the global price of food, the regime opened the door widely for foreigners who wanted to acquire large-scale farms. These farms do not hurt their crony businesses but they do harm poor subsistence farmers. Vast tracts of lands have been sold to foreigners at ridiculously cheap prices, often displacing locals and their way of life.

Contrary to the government rhetoric, the motivation for opening up the agricultural sector has nothing to do with economic growth but everything to do with politics – to silence critics, particularly in the donor community who persistently question EPRDF’s credibility in attracting FDI. In essence, hundreds of thousands of poor farmers were evicted to make way for flower growers and shore up the government’s image abroad. This tactic seems to be working so far. Earlier this year, Ethiopia received its first credit rating from Moody’s Investors Service. In the last few years, in part due to rising labor costs in China and East Asia, several manufacturers have relocated to Ethiopia.

Addis’ construction boom as a smokescreen

Crony businesses and flower growers may have created some heat but certainly no light in Ethiopian economy. EFFORT and MIDROC were in action for much of the 1990s and early 2000s but GDP growth was not satisfactory during that time. In fact, since other private businesses were in dismal conditions (and hence domestic market size is very limited), even the crony businesses encountered challenges in getting new business deals.

The setbacks in political front during the 2005 election shifted EPRDF’s strategies to economic front to urgently register some noticeable growth. This partly explains the motives behind the ongoing construction rush in and around Addis Ababa. In several rounds of interviews on ESAT TV, former Minister d’etat of Communications Affairs, Ermias Legesse, provided interesting accounts of cronyism surrounding Addis’ explosive growth and its tragic consequences for Oromo farmers.

It is important to understand the types of construction that is taking place around or near Addis. First, private property developments by crony estate agents mushroomed overnight. A lion’s share of land expropriated from Oromo farmers were allocated to these regime affiliates through dishonest bids. Luxury houses are built on such sites and sold at prices no average Ethiopian could afford, except maybe those in the diaspora. The latter group is being targeted lately due to shortages of hard currencies.

Second, EPRDF politicians and high ranking military officers own multi-storey office buildings, particularly aimed at renting to NGOs and residential villas for foreign diplomats who can afford to pay a few thousand dollars per month. It is a known fact that the monthly salary cap for Ethiopian civil servants is around 6000 birr (about $300). As such, that these individuals could invest in such expensive properties underscores the extent of the daylight robbery that is taking place in Ethiopia.

Third, the government was engaged in massive public housing construction but under extremely chaotic circumstances. The condominium rush in Addis is akin to the Dergue regime’s villagization schemes in rural Ethiopia. Families are uprooted from their homes without any due consideration for their social and economic well-being.

Most households that once occupied the demolished homes in Addis Ababa’s shantytowns made a living through informal home businesses such as brewing local drinks and preparing and selling food at prices affordable to the poor. It was clear that the condominiums were not suitable for them to continue doing such businesses. The construction of the public houses was financed by soft loans from various donor agencies to be sold to target households at affordable prices. However, the government often priced them at the going market rates for condos.

As a result, the poor households simply rented out the properties to those who could afford, while struggling to find affordable houses for themselves. Solving the public housing crisis was never the government’s intention in the first place, as they were only interested in creating business opportunities for their crony construction companies.

Fourth, roads and railway networks are by far the most important large-scale public sector construction projects taking place in Addis. There is no doubt that Addis Ababa’s crowded roads, equally shared by humans, animals and cars, need revamping. But, what is happening in the name of building roads and railways simply defies belief. First, the sheer scale and magnitude as well as the obsession with construction makes the whole undertaking look suspicious. Every time I travelled to Addis, I witness the same roads being constructed and then dug up to be reconstructed over and over again.

The ulterior motive behind these projects is nothing more than expanding TPLF’s business empire and benefit crony allies. Having exhausted opportunities within the existing perimeter of Addis, the so-called master plan had to be crafted to enlarge the size of “the construction site” by a factor of 20 to ensure that the cronies will stay in business in the foreseeable future. In effect, the large-scale construction projects are being used to siphon off public funds. And there seems to be no priority or accountability in the whole process from the project inception, planning to implementation.

Lies and damn lies

The construction boom in Addis serves as a two edged sward. On the one hand, the funds generated from selling Oromo lands to private property developers adds to the ever-expanding business empire of Tigrean political and military elites. On the other hand, the appearances of several high-rise buildings and complex road networks give the impression that Ethiopia is witnessing an economic boom. The target audience for the latter scenario is foreign journalists and the diplomatic community in Addis Ababa, some of whom are so gullible that they fall in love with ERDF’s economic “miracle” from the first aerial view even before landing at the Bole airport.

The fact remains however: no such economic miracle is actually happening in Ethiopia. A pile of concrete slabs cannot transform the economy in any meaningful way. After all, buildings and roads are only intermediaries for doing other businesses. For instance, it is not enough to build highways and rural roads – a proportionate effort is required to enhance production of goods and services to move them on the newly built roads in such a way that the roads will get utilized and investments made on them get recovered. Otherwise, the roads and buildings can deteriorate without giving any service, and hence more public money would soon be required to maintain them. This is exactly what is happening in Ethiopia.

Meanwhile, the EPRDF has been engaged in a frantic effort to generate lies and damn lies to fill the gap between the rhetoric and the reality of Ethiopia’s economy. The government-controlled media has been used for extensive propaganda campaign to create a “positive image” in the eyes of ordinary citizens. They literally compel viewers or listeners to see or feel things that do not exist on the ground. The Ethiopian television zooms onto any spot of land with a colony of green grass or lush crop fields to “prove” the kinds of wonders the government is engineering.

Barring rain failures, much of Ethiopia’s lush-green countryside has a decent climate for agriculture. But the EPRDF regime tries to convince the public that anything positive that occurs in the Ethiopia is because of its economic policies. But, as evidenced in ongoing multifaceted grievances around the country, the government is fooling no one else but itself (and perhaps a few gullible individuals in the diplomatic community).

Its lies also come in the form of dubious economic statistics, which are generated in such a way that EPRDF could report double-digit economic growth year after year. The story of the double digit economic growth rate in Ethiopia has been such that a lie told hundreds of times, no matter how shambolic the numbers are, is becoming part of the western vernacular. Donors often point to the abundance of high-rise buildings and impressive road networks in Addis Ababa in regime’s defense.

In a brief conversation, it is not possible to take such casual observers through details of the kind I have attempted to narrate in the preceding paragraphs. And, unfortunately for millions of Ethiopia’s poor, in the short run the government’s lies and crony capitalism may continue to ravage the country’s economy until it begins to combust from within.

*The writer, J. Bonsa, is a researcher-based in Asia. Photo courtesy of Addis Food Not Bombs – Ethiopia.

http://www.opride.com/oromsis/news/3762-the-myth-of-ethiopia-s-crony-capitalism-and-economic-miracle

A UK High Court ruling allowing judicial review of the UK aid agency’s compliance with its own human rights policies in Ethiopia is an important step toward greater accountability in development assistance.

Ethiopia: UK Aid Should Respect Rights

By Human Rights Watch, 14th July 2014

(London) – A UK High Court ruling allowing judicial review of the UK aid agency’s compliance with its own human rights policies in Ethiopia is an important step toward greater accountability in development assistance.

In its decision of July 14, 2014, the High Court ruled that allegations that the UK Department for International Development (DFID) did not adequately assess evidence of human rights violations in Ethiopia deserve a full judicial review.

“The UK high court ruling is just a first step, but it should be a wake-up call for the government and other donors that they need rigorous monitoring to make sure their development programs are upholding their commitments to human rights,” said Leslie Lefkow, deputy Africa director. “UK development aid to Ethiopia can help reduce poverty, but serious rights abuses should never be ignored.”

The case involves Mr. O (not his real name), a farmer from Gambella in western Ethiopia, who alleges that DFID violated its own human rights policy by failing to properly investigate and respond to human rights violations linked to an Ethiopian government resettlement program known as “villagization.” Mr. O is now a refugee in a neighboring country.

Human Rights Watch has documented serious human rights violations in connection with the first year of the villagization program in Gambella in 2011 and in other regions of Ethiopia in recent years.

A January 2012 Human Rights Watch report based on more than 100 interviews with Gambella residents, including site visits to 16 villages, concluded that villagization had been marked by forced displacement, arbitrary detentions, mistreatment, and inadequate consultation, and that villagers had not been compensated for their losses in the relocation process.

People resettled in new villages often found the land infertile and frequently had to clear the land and build their own huts under military supervision. Services they had been promised, such as schools, clinics, and water pumps, were not in place when they arrived. In many cases villagers had to abandon their crops, and pledges of food aid in the new villages never materialized.

The UK, along with the World Bank and other donors, fund a nationwide development program in Ethiopia called the Promotion of Basic Services program (PBS). The program started after the UK and other donors cut direct budget support to Ethiopia after the country’s controversial 2005 elections.

The PBS program is intended to improve access to education, health care, and other services by providing block grants to regional governments. Donors do not directly fund the villagization program, but through PBS, donors pay a portion of the salaries of government officials who are carrying out the villagization policy.

The UK development agency’s monitoring systems and its response to these serious allegations of abuse have been inadequate and complacent, Human Rights Watch said. While the agency and other donors to the Promotion of Basic Services program have visited Gambella and conducted assessments, villagers told Human Rights Watch that government officials sometimes visited communities in Gambella in advance of donor visits to warn them not to voice complaints over villagization, or threatened them after the visits. The result has been that local people were reluctant to speak out for fear of reprisals.

The UK development agency has apparently made little or no effort to interview villagers from Gambella who have fled the abuses and are now refugees in neighboring countries, where they can speak about their experiences in a more secure environment. The Ethiopian government’s increasing repression of independent media and human rights reporting, and denials of any serious human rights violations, have had a profoundly chilling effect on freedom of speech among rural villagers.

“The UK is providing more than £300 million a year in aid to Ethiopia while the country’s human rights record is steadily deteriorating,” Lefkow said. “If DFID is serious about supporting rights-respecting development, it needs to overhaul its monitoring processes and use its influence and the UK’s to press for an end to serious rights abuses in the villagization program – and elsewhere.” Read @http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/07/14/ethiopia-uk-aid-should-respect-rights

by Alemu Hurissa

Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) minority led regime has ruled Ethiopia for 23 years. During the years TPLF has been in power, they have used various methods to control everything in the country. One of these methods was false accusations against individuals or groups of sympathizing with the Oromo Liberation Front although the question of these individuals or groups has been based on the constitution of the country.

At the beginning when they came to power after overthrowing the Derg regime they promised to democratize the country, however they didn’t take time before they started targeting those who didn’t support their ideas as dissenters were subjected to torture and terrible sufferings in mass detention centres across the country. Over the last 23 years they have been in power, they have carried out unimaginable destruction against human life and natural resources in the country particularly in Oromia region. For instance destruction of Oromia forests and other natural resources as well as the killing of Oromo students, farmers and Oromo intellectuals in all parts of the region.

In December 2003 the government security forces massacred more than 400 Anuak Civilians in Gambella region as reported on January 8, 2004 by Genocide Watch, a US based Human Rights group. Police violence in Tepi and Awassa in the Southern Nations-Nationalities, and Peoples (SNNP) regional state, resulted in the death of more than one hundred civilians and the arrest of hundreds. The Human Rights Watch report 14 January 2003 termed it as Collective Punishment.

War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity in the Ogaden area of Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State, June 2008 and 19 October 2006, the Ethiopian police massacred 193 protesters in violence following last year’s disputed elections, an independent report says. These are very few among many such incidents that I have elected to mention as an example of TPLF security forces’ atrocious acts against innocent people in different parts of the country. The victim of these brutal acts range from very young children to the elderly people by age categories. For example, there was a report that an eight years old child was killed by federal police in Gudar in May 2014.

If any individual does not agree and support their agenda, automatically that person is a member of OLF, according to Woyane regime’s definition. For example, Bekele Gerba, who was a lecturer at Addis Ababa University was arrested in 2010 by the TPLF-led regime simply because he clearly depicted the true evil nature and behavior of TPLF and its members. He said the land inOromia is a private property of the ruling party members. If they want they will sell it or they will give it to the people who support them and these are people who got rich in a way that cannot be reasonably explained. Many Oromo prisoners testified about Oromo people suffering in jail after they have been released or escaped from prison. To name some of them, Ashenafi Adugna and Morkaa Hamdee are among the victims who suffered at the hands of Woyane security forces while they were in prison. Many innocent Oromo people sentenced to life term and death without any evidence that shows their involvement in any criminal act. What happened in the Oromia region against Oromo University and high school students by federal police as reported by the BBC and other mass media is evident to mention as an example.

In general, the brutal acts against Oromo people by TPLF security forces have never been witnessed anywhere in the world. This clearly depicts what the TPLF government and its party members stand for and lack of their perception about personal worth, and the contempt they have for a human being. One can be quite sure that oppression cannot continue forever, and the dark time for Oromo people shall be replaced with justice and freedom.

In a democratic country, the people have right to express themselves freely in accordance with the constitution and the laws of the country; but in Oromia, there is no freedom of speech. No one in Oromia can freely express him/herself. In oromia, the will of the people has been replaced by the will of the TPLF regime. What has been unfolding for the last 23 years in Oromia region is that the TPLF regime is busy fabricating false documents that are used by the brutal regime’s security forces to incriminate, intimidate, persecute, harass, arrest, torture and kill the innocent Oromo people. So for Woyane democracy means not to allow people their freedom of expression, intimidating, persecution, harassment, arresting, torture and killing innocents in cold blood.

Generally, woyane is a tyrant regime which uses power oppressively and unjustly in a harsh and cruel manner against Oromo people to keep itself in power as long as they could, but I strongly believe that the crimes woyane carried out against Oromo people as a part of its lust for wealth and power will not keep them in power rather it shall hasten the time the Oromo people will achieve freedom. It would be wrong to say woyane will stay in power while using excessive force of power and committing crimes against innocent Oromo people in horrible and oppressive character. What the government is doing now by the name of development is meaningless and inhuman; how one can bring development while exposing people to suffering and death is beyond anyone’s imagination.

Playing game with human life to gain wealth and acquire luxurious life in modern time by robbing and plundering the Oromo people’s wealth is simply unacceptable. The TPLF regime should have been grateful to the Oromo people instead of making Oromo people live a horrible life; because the better life enjoyed by the TPLF politicians came as a result of Oromia’s natural resources. Instead of displacing Oromo farmers, dismissing, arresting and killing Oromo students and dismissing Oromo workers from their job, would have given more respect and value for all Oromos. The problem is that the TPLF regime and itsSatellites parties like OPDO never understand the importance of Oromo people and Oromia region in Ethiopia. Oromia is bleeding since woyane has come to power, because woyane governed Oromia by using excessive force and violence.

All countries that have diplomatic relationships with Ethiopia have also played a major role in keeping woyane in power, because woyane has received too much money from these developed countries under the name of humanitarian assistance which woyane uses to buy weapons to brutally crackdown Oromo students, farmers and scholars. Under woyane’s political system there is no legal and moral right, in general, no rule of laws and justice.

On May 2, 2014, BBC reported that the security forces of the regime in Ethiopia had massacred at least 47 University and high school students in the town of Ambo in Oromia region. Human rights watch and other Non- governmental organizations also reported how the Ethiopian government abuses its own citizens for the benefit of the ruling party members.

The inhuman acts of TPLF regime against the Oromo students shows that it does not only kill students but also TPLF wants to kill the whole young generation psychologically which is their evil strategy and tactics in fact became in vain as Oromo students have continued their struggle for justice in Oromia region. We, Oromo should stand together to bring the perpetrators of massacre in Ambo town and other Universities to justice. It is true that as long as Woyane keep getting money and other facilities from developed countries; as developed countries also give priority for strategic interest than human right, it will be like climbing the top of a mountain; however, we should not let them to continue their inhuman action. What we have to know is that those students who have been massacred by woyane security forces could have been mine, our relatives or children. These students are hope of their family, Oromo society and the Oromia region in general.

TPLF-led regime in Ethiopia never understand the value of human being, what democracy and freedom of speech means because since they came to power, they have never learned from their mistakes rather than its political system goes from bad to the worst. Atrocities against our people have to continue because of just addressing the human right issue and the question of justice and freedom. So, to change the woyane’s oppressive and horrible political system in Oromia, all people who believe in justice and who know the value of human being should stand with the Oromo people and say no to the fascist and terrorist government of Ethiopia. Killing Oromo University and high school students in April and May 2014, beating and arresting students and local people, when the students and local people protested peacefully against the expansion of Finfinne and the eviction of Oromo farmers from their indigenous land is a proof that the regime in Ethiopia is being the fascist and terrorist regime. Woyane is always looking for a scapegoat for their evil actions and behaviors, but it is only woyane and its members who are responsible and will be held accountable for the crimes they committed against innocent Oromo people.

Fake leadership in Ethiopia have destroyed the Oromo people, and the constitution and the law of the country is always in favour of the TPLF regime, not the Oromo people. The TPLF regime is simply the worst government I have ever seen in the modern era.

At the end of my piece of writing, I challenge all Oromos to unite, as unity is strength and to contribute whatever we can to bring down woyane and its members from power and to bring justice and freedom to Oromia and I challenge and hope developed countries also will stop financial and technical support to terrorist regime in Ethiopia.

Read more@

http://ayyaantuu.com/horn-of-africa-news/oromia/what-does-democracy-mean-for-tplfeprdf/

Related articles and references:

By Firehiwot Guluma Tezera

When we talk about election in Ethiopia, the 2005 national election has become foremost as previous elections under both Derg and EPRDF were fake. The national election of 2005 has shown a hint of democracy until election date in Addis Ababa but in regions it was until one month before the voting date. The ruling party has been harassing the opposition and has killed strong opposition candidates. In Addis Ababa the hint of democracy disappeared after the ruling party diverted the election results.

Having no other option than forcefully suppressing the anger of the people caused by its altering of election results, the ruling party intensified the harassment and killing. So the outcome for the opposition was either to go to prison or follow the path given by EPRDF. Election 2005 ended in this manner.

The plan of the ruling party to give a quarter of the 540 parliamentary seats to the opposition and to minimize outside pressure and to restart the flow of foreign aid was unsuccessful. The election has made the party to assess itself. Even though it was widely accepted that EPRDF had altered the outcome of the 2005 election and had not anticipated the outcome, many have expected that the party will correct its mistakes. But the party says it has learnt from its mistakes but it made the following strategies:

Measures taken post 2005 election

EPRDF used the above strategies for the preparation of 2010 elections. By implementing the strategies it has succeeded in increasing its members but they were not genuine supporters but they supported for benefits. When such kind of members increase, it becomes difficult to fulfill their benefits and at the end they become corruptionists. And they will become the ultimate enemies of the party.

The strategies mentioned above have enabled the party to claim to be winning 99% of the votes. Thenext day the then prime minister said” the people have given us 5 years contract believing that we have learnt from our past mistakes. This is a big warning for us. If we don’t live to their expectation they will take away their votes.” This was his scorning speech. But both the people and they know how they won and the 2010 election was declared error free.

The Oromian Economist makes research, discusses, analyses and informs on leading issues of Economics, freedom, liberty, development, culture and change that are relevant to Oromia, Africa, developing world and the related humanity and civilization.

For the minority TPLF led Ethiopian regime, who has been already selling large area of land surrounding Addis Ababa even without the existence of the Master Plan, meeting the demands of the protesting Oromo students means losing 1.1 million of hectares of land which the regime planned to sell for a large sum of money. Therefore, the demand of the students and the Oromo people at large is not acceptable to the regime. It has therefore decided to squash the protest with its forces armed to the teeth. The regime ordered its troops to fire live ammunition to defenceless Oromo students at several places: Ambo, Gudar, Robe (Bale), Nekemte, Jimma, Haromaya, Adama, Najjo, Gulliso, Anfillo (Kellem Wollega), Gimbi, Bule Hora (University), to mention a few. Because the government denied access to any independent journalists it is hard to know exactly how many have been killed and how many have been detained and beaten. Simply put, it is too large of a number over a large area of land to enumerate. Children as young as 11 years old have been killed. The number of Oromos killed in Oromia during the current protest is believed to be in hundreds. Tens of thousands have been jailed and an unknown number have been abducted and disappeared. The Human Rights League of the Horn of Africa, who has been constantly reporting the human rights abuses of the regime through informants from several parts of Oromia for over a decade, estimates the number of Oromos detained since April 2014 as high as 50, 000

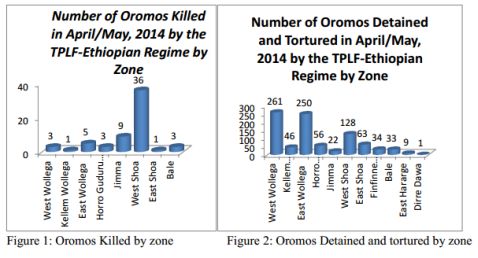

In this report we present a list of 61 Oromos that are killed and 903 others that are detained and beaten (or beaten and then detained) during and after the Oromo students protest which begun in April 2014 and which we managed to collect and compile. The information we obtain so far indicates those detained are still in jail and still under torture. Figure 1 below shows the number of Oromos killed from different zones of Oromia included in this report. Figure 2 shows the number of Oromos detained and reportedly facing torture. It has to be noted that this number is only a small fraction of the widespread killings and arrest of Oromos carried out by the regime in Oromia regional state since April 2014 to date. Our Data Collection Team is operating in the region under tight and risky security conditions not to consider lack of logistic, financial and man power to carry the data collection over the vast region of Oromia.

Related References:

Why has Africa’s growth failed to translate into adequate job creation? Key insights from Unctad’s Economic Development in Africa report 2014*

Africa has a huge problem with unemployment, particularly youth unemployment. It has experienced a high rate of population growth, which has the potential to be a demographic dividend but only if there is sufficient investment in jobs, skills and education.

Essentially, the continent hasn’t produced enough investment and growth in the domestic economy. Public sector investment has been low, and foreign direct investment has largely been channelled into the sectors where the big returns are – oil, gas and minerals.

The difficulty is that these sectors are not very good at generating economic benefits outside a very small enclave. They are not labour intensive so they don’t create large numbers of jobs and benefit the wider economy. Investment needs to support sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing and industry that have the potential for higher growth and job creation. This type of employment creation will be key to the future of the continent’s growth.

What lies behind this failed investment strategy?

Partly it is the advice many African countries have had from Bretton Woods Institutions [World Bank and International Monetary Fund]. It is also partly a risk-averse strategy so they don’t find themselves in a terrible situation should another global financial crisis arise. But it is also fundamentally about a lack of political focus on building capacity, diversifying economies and recognising the need to create more employment.

What does the report have to say about the sectors where employment has declined, and risen?

Broadly speaking, because in Africa we’ve seen both population growth and a failure to upgrade traditional sectors like agriculture there’s been a high degree of rural-urban migration. Lots of people are moving from subsistence agriculture into urban activities which are largely informal and survivalist. This tends to be low-paid, vulnerable employment. This type of work makes up about 80% of total employment in many African countries.

The report highlights the unusually high level of employment and growth in the services sector in Africa, relative to its stage of development. However for this sector to see long-term growth and adequate job creation, there needs to be big leaps in investment in basic infrastructure. There are opportunities in agriculture too. While in the long run many people will still move from rural to urban areas, if we invest and raise productivity we can raise the incomes for those in the sector.

Are there any misunderstandings about the relationship between growth, investment and employment in Africa?

Often this relationship is understood as being a virtuous circle. We argue that growth in Africa has failed to translate into broader development gains such as employment.

What is key to this nexus is the role of the state. Governments have to be more aware that different types of economic activity involve different types of employment intensity. While the services sector is producing more job opportunities than the extractive sectors there still needs to be more investment directed towards industries such as manufacturing and agriculture. Africa has a relatively weak private sector so the state needs to have a much more prominent role in mobilising investment into job-rich sectors.

*By Junior Davies, an economist at the division on Africa, least developed countries and special programmes of Unctad

@http://4globaldevelopment.wordpress.com/2014/07/07/booming-economies-are-not-boosting-employment-in-africa-why-global-development-professionals-network-the-guardian/

Read more@

http://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2014/jul/03/unctad-report-africa-economics-employment?CMP=twt_gu

Theorizing Development

From historical perspectives, the urgency underlying the contemporary development quest of developing economies has been recognised for the last seven decades. Of course, this should not be considered as that there were no problems of development prior to 1940’s. However, paralleling the increasing for economic self-determination and development of developing economies, there has been a tremendous growth in intellectual activity concerning the development problems.

The past 70 years have also witnessed a gluttony of models, theories, and empirical investigations of the development problem and the possibilities offered for transforming Asia, African, Latin American, and Caribbean nations. This body of knowledge as come to be known in academics and policy circles as development economics.

In these perspectives development is discerned in the context of sustained rise of an entire society and social system towards a better and ‘humane life’. What constitutes a better and humane life is an inquiry as old as humankind. Nevertheless, it must be regularly and systematically revised and answered over again in the unsteady milieu of the human society. Economists have agreed on at least on three universal or core values as a discernible and practical guidelines for understanding the gist of development (see Todaro,1994; Goulet, 1971; Soedjatmoko, 1985; Owens, 1987). These core- values include:

Sustenance:

the ability to meet basic needs: food, shelter, health and protection. A basic function of all economic activity, thus, is to provide a means of overcoming the helplessness and misery emerging from a lack of food, shelter, health and protection. The necessary conditions are improving the quality of life, rising per head income, the elimination of absolute poverty, greater employment opportunity and lessening income inequalities;

self-esteem:

which includes possessing education, technology, authenticity, identity, dignity, recognition, honour, a sense of worth and self respect, of not being used as a tool by others for their own exigency;

Freedom from servitude:

to be able to choose. Human freedom includes emancipation from alienating material conditions of life and from social servitude to other people, nature, ignorance, misery, institutions, and dogmatic beliefs. Freedom includes an extended range of choices for societies and their members and together with a minimization of external restraints in the satiation of some social goals. Human freedom embraces personal security, the rule of law, and freedom of leisure, expression, political participation and equality of opportunity.

Sustained and accelerated increase and change in quantity and quantity of material goods and services (both in absolute and per capita), increase in productive capacity and structural transformation of production system (e.g. from agriculture to industry then to services and presently to knowledge based (new) economy), etc. hereinafter economic growth is a necessary if not a sufficient condition for development.

As elaborated in Hirischman (1981) and Lal (1983), this corpus of thought and knowledge denotes economics with a particular perspective of developing nations and the development process. It has come to shape the beliefs about the economic development of developing countries and policies and strategies that should be followed in this process. While development economics goes beyond the mere application of traditional economic principles to the study of developing economies, it remains an intellectual offspring and sub discipline of the mainstream economics discipline. The growth in economic knowledge and the corresponding intellectual maturation of development thought and policy debate has led to the appearance of various perspectives of thought on the theory and reality of development and underdevelopment within the same discipline of development economics. The two main paradigms are neo-classicals (orthodox), and Political economy (neo-Marxists). There are also eclectics.

Copyright © The Oromianeconomist 2014 and Oromia Quarterly 1997-201 4. All rights reserved. Disclaimer.

Development: What role for Institutions

The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.

Keynes, John Maynard

Introduction

The force of human reductionism that had assaulted on Oromia’s history, civilisation, politics and economy for many centuries in the last three Christian millenniums and particularly of the last two centuries has continued in the new millennium to enfeeble the endeavours of its people towards progress and development.

Oromia is not the poorest of the nations of the world in resources but it is one of the most underdeveloped, characterised by thwarted advancement, declined progress and cataclysm.

In Oromia today immense agricultural potential, mineral wealth and human capital coexist with some of the lowest standards of living in the world. Part of the problem lies in the nature of the economic change the Abyssinian colonialism fostered in Oromia. The Oromo economy has been distorted to serve the Abyss interest and needs.

Oromos are the most brutalised and humiliated in modern history. The genocidal treatments, which Oromos have received from Abyssinians, have been as gruesome as anything experienced by Jews, Native American and native Australians and the Armenians received from the Nazi, Europeans, white Americans, and the Ottoman Turkey respectively. Oromos have also been humiliated in history in ways that range from the level of slavery, segregation and treated as second-class citizens in part of their own country to the present day in spite of being numerically the majority and geographically the largest territory.

In the early 1990s the old Amhara settler colonialism (Nafxanyaa system) was substituted by Tigrean ‘federal colonialism’ (neo- nafxanyaa system) the facet of exploitation seemed to take on new dimensions. In fact, the pattern of colonisation and domination has remained the same since it instated century ago with the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, which had approved the scramble for Africa among European colonial powers. It was a time when the cruel Abyssinian Empire was given an ordinance of Christianising and ‘civilizing’ the Oromos; though it is a historic derision how a backward and barbaric empire was to ‘civilize’ the society of prime civilisation, high culture and social structure, the ‘natives’, whose development levels and potentials were diverse and by far advanced.

The very idea of Christianising and civilizing was an external imposition often upheld by external protagonists. In the pre 1974 Ethiopia, this took the form of substantial military and economic aid from the US America and Europe. During the Cold War era, the mission of oppression of the Oromos maintained and supported by fresh military and economic aid from the then Soviet Union scheme of spreading its sphere of dominion and its ideology to Africa. In the contemporary ‘new world disorder’, the support has got new momentum in which the old Christian missionaries are replaced by an army of western neo-classical economists who peddle a ‘free market’ ideology, which they hope, will take care of the imprisoned market agents, in this case the Oromos.

According to the new Gospel, the Tigrean colonizers are given the mandate and the necessary financial backing to pursue ‘economic liberalization’ while keeping strict control that Oromia remains the Abyssinian colony. The liberalization agenda has served as a precursor of the making of Tigrean version of crony capitalism or more appropriately advanced feudalism in the age of economic globalisation. It is alien to Adam Smith’s invisible hand, social justice and the free-market ideals of relying on legal contracts, property rights, impartial regulations and transparency. It is no wonder that the political and economic prescriptions that the Ethiopian colonial rules implemented and or pretend to implement are in line with the advice of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank and The US administration’s The Horn of Africa Initiative all of which have exacerbated the problem of the Oromo nation. It has also betrayed the ideals of free market, social justice, self-determination and human rights.

The sorrowing fact is that shared interest and solidarity between the West and the Abyssinian colonizers are impoverishing the people. Pretentious and ill-conceived measures are being taken in the name of free market and above all development. Currently, there are a number of regime-sponsored ‘associations’ of this or that ‘Region/State’s Development’ anti-terrorism, poverty alleviation, renewal process, revolutionary democracy, etc. Given this, the people’s last resort is to defend their own interests is the exit option or to retreat from the colonizers. What has become more apparent than ever is the need to rely on the Oromo initiatives to solve the problems of the Oromo. The Oromo poor need to defend themselves from the bogus free market invaders and their phoney local allies. This is necessary, since, in the absence of property rights, social justice, and individual and social freedom and democracy, no free market economic gimmickry is able to reserve the tragedy of the oppressed. It is within this context, that we discuss, how the Ethiopian colonial rules, in collaboration once with international socialism and now with the global capitalism has impoverished and underdeveloped one particular community in Africa, the Oromo nation.

Sclerotic to development: The Abyssinian Colonial Occupation and Its Alliances

Economists are inspired to point out the weight of political factors, captured by the term ‘governance’ and its role in economic development. Concerns about political factors in economic development is revitalized because of the dearth of economic development reform and structural adjustment programs to yield definite success and prosperity, particularly, in Africa. The main problem pointed out is ‘poor governance’ (World Bank, 1989; Moore, 1992). There are three different aspects to the notion of governance that can be identified as:

The form of political regime (independent, colonial government, multi-party democracy, authoritarian, etc.),

The process by which authorities exercised in the management of the country’s economic and social resource; and’

The willingness, the competence and the capacity of the government to design, formulate, and implement genuine development policies, and, in general to discharge development and government functions.

As there is no antithesis concerning the conviction that ‘good’ governance is an important and desirable ingredient of development, scholars are cautious not to attach specific regime type and political reforms to good governance. Broadly, however, good governance is legitimated by developmentalist ideology while poor governance is characterized by ‘state elite enrichment ‘ (Jackson and Rosberg, 1984), the ‘rent seeking society’ (Krueger, 1974) or ‘politics of the belly’ (Bayart, 1993;Tolesa, 1995) such as Ethiopia, Nigeria and Zaire). The latter in fact are characterized by sclerotic behaviours and are obstacles to development.

The Oromia’s underdevelopment (negative development) and its associated problems are never going to be understandable to us, much less contain it, as long as we persist to ponder it as a mere as an economic enigma. What is before us momentarily is in essence an enigma of political colonialism whose economic after-effects are severe.

Not only the problem is basically political and colonial in character. It arose largely from Abyssinian imperial conquest and its associated colonial disposition, which is characterized by reliance on sheer force, state terror, genocide, plunder, authoritarianism and violence.

The story goes back to the days of the Abyssinians crossed the Red Sea and seized the territory and resources of the Cushites ( Bibilical Ethiopia, the present Horn of Africa and Oromia) making concerted aggression on the latter’s history and culture in the name of settlement and civilizing the ‘non-believers.’

As it is discussed above and elsewhere, in the first millennium BC the Abyssinian group crossed the Red Sea from South Arabia (source: the debtras’ records and memories of Abyssinian high school history text book) to the present North East Africa to conquer and resettle the land occupied by endogenous Oromo and the other Cushitic people. Recent research recognises that the Semitic culture of the Abyssinian empire’s northern highlands was built on the Cushitic base for which not genuine credit has been given, and the Axum obelisks which were attributed to the (Sabeans Abyssinians) do not have corresponding existence on the Arabian peninsula while they are abundant in the Nile valley stretching from Egypt to ancient Kush in today’s Sudan. This most probably indicates that the earlier phase of Axum civilization was predating the Sabean infiltration/invasion.

Cleansing as a policy was initiated to conquer the Cushite territories. The territory they conquered was divided among numerous Abyss chiefdoms that were as often at war with each other as with Oromo and the entire Cushite. The population of conquered territories were considered as dangerous thus; Abyssinian cleansing, up rooting, forced labour and killings of the vanquished were conducted as the means of crushing resistance, securing the conquered territories and even to expand their occupation further. Though the Abyssinian gained some territories and resettled in the northern highlands of the Oromo and other Cushitic regions among others Afar, Agau, etc., their expansion was checked for a long time in history by wars of resistance and liberation they encountered by the endogenous people. These wars of resistance led to a decisive victory for Oromo, Afar and Somali nations particularly from 12th to the second half of 19th century. As a result of such a defeat Abyssinians started to wage particularly anti-Oromo propaganda battles to alert themselves and attract foreign support against the Oromo. The derogative name ‘Galla’ and the ‘16 century Oromo migration’ were all the Abyssinian fabrications and to serve the war against Oromo. In fact, the Oromo oral history shows that the 16th century was a massive Abyssinian further southward migration and intensive campaign to entirely control Oromia and other territories. For the Oromo this period was characterized by political and military dynamism and at the same time it was a period of victory, massive dislocations, rehabilitation and displaced communities returning home.

According to M. Bulcha (see Oromo Commentary), it was only during the second part of the 19th century that the Abyssinians ultimately succeeded to make significant in roads into the Oromo territory. Tewodros (also known in different names Hailu, Kassa, Dejazmach, Ras, etc., as other Abyssinian shiftas and present Woynes, is on record for his brutish hostility towards the Oromo nation. He was not the first or the last of his kind. They were many before and after him, for concrete evidence even today, this time and this second. All of them have been gangsters of very abnormal characters and Abyssinian detested figures. The Abyssinians remembered Tewodros and his type not only as the romanticized hero figures but also portrayed them as a modernises. Tewodros the lunatic and bandit declared and conducted a war of extermination against the Oromo. In order to help them to bargain for the western support, he and all his type including Yohannes, Menelik, Haile Sellasie, Mengistu and currently Meles declared anti-Islam and anti-Muslim nations. They mobilized all their resources and the entire Abyssinia (Amhara &Tigre) against the Oromo to achieve their goal. Tewodros made every effort to obtain the European military support claiming his fictions of Christian identity and ideology (the then dominant political ideology though he had not any biblical ethics and values, not at all). Tewodros is a symbol and an element of Abyssinian barbarism that was conducted at particular historical stage (1850-1868). Such barbarism has been conducted since the Axumite period (3000 years) but has never achieved its ultimate goal of elimination of the entire endogenous people of the North-East Africa. But it eliminated millions of and it thwarted the civilisations of Cushite people. They have used all the devastating means the: Christian civilizing ideology, European army, settler colonialism, Soviet Socialism, Stalin collectivisation, Mengistu’s villegisation, and America’s structural adjustment, terrorism, etc. They have always tried to change names after names for the same ugly & old expansionism, feudalism and empire (the legendary land of Sheba, Ethiopia, Ethiopia first, socialist Ethiopia, republic, mother land, federal etc.). The very name Ethiopia is Hellenistic Greece. It was the name used in the ancient Greece occupation (before Romans) of North Africa people and southward expansion. This name was colonialism from the beginning and it has been, it is and it will be. It is not African in origin as the people who invented it. This name was adopted and maintained to conquer the entire Cush and then the entire Africa in the shadow of christianisation. It is a sinister name that has no boundary and ethnic identity. It is not only the conquered people of North-East Africa but also all Africanists that must understand, including its sinister philosophy. It was designed and adopted to deconstruct an endogenous African identity.

One implication of the doctrine of Abyssinian ‘civilizing mission’ was that the Oromos needed to be ruled by Abyssinians and could not responsibly be granted civil liberties. Authoritarian as it has always been, the Abyssinian colonial rule in Oromia whether under Menelik II, Haile Selassie, Mengistu and currently under Meles has been characterized by the ‘politics of the belly.’ The underlying ethos remains self-aggrandizement and those elites are alien to growth whereas corruption, brutality, inefficiency and grotesque incompetence have tainted their politics. Time and again, they siphoned off Oromia’s wealth and indulged in conspicuous consumption and stashing millions of dollars in remote secret accounts in Europe, America and Asia. Scholars understand that development is about the future. However, the Abyssinian elites are living for the present. They came for quick self enrichment. The Oromos have no opportunity to invest in their country. They disowned everything.

While the Abyssinian colonial settlers in Oromia do no want and support policies that promote development, they find military and other forms of support abroad to stay in power. In more than one time, this force of underdevelopment has been strongly reinforced by external forces (Holcomb and Ibssa, 1990). Despite generous foreign assistance, this hardly commanded legitimacy to mobilize the colonized masses behind their rule. To the contrary, people who have waged legitimate struggle to reclaim their freedom, cultures and history has fiercely resisted their rule.

As it has been discussed elsewhere, Oromos have their own political power, which was fully operational before they were colonized and occupied by Abyssinians put under the strict control of Ethiopian empire state. Their political system is based on the Gadaa (Gada) system. The Gadaa system has been the foundation of Oromo civilization, culture and worldview (Jalata, 1996). The Gadaa political practices manifested the idea of real representative democracy with checks and balance, the rule of law, social justice, egalitarianism, local and regional autonomy, the peaceful transfer of democratic power, etc. (Jalata, 1966). The Gadaa political system also facilitated property rights, stability, and the expansion of free trade, commerce, improved farm techniques and permanent settlements, gradual diversification of division of labour. The Gada state was non-taxing state. Military was not the focal point, only defensive which is democratic. It was the opposite of expansionist, imperial, genocide or conquering state, e.g. Roman, Sparta, Abyssinian and Serbia, etc.

One of the distinctive virtues of Gadaa state was the weight of civilian power as compared to military power, military aristocracy was practically absent and in normal times, the army executed only an inconspicuous, if not nonexistent, political function. The military aristocracy was not the focal point of society. War had rather a defensive mission.

Nonetheless, particularly since the last decades of the nineteenth century, the Abyssinian colonial rule and its state disallowed the Gadaa political system and expropriated the Oromo basic means of subsistence, such as land cattle while it established an Ethiopian system of rule over Oromia. The Oromo commerce and industrious activities were not only discouraged but also ridiculed and obtained the lowest social status. Productive relations were imposed through the process of commodity production and extraction between those who control or own the means of production, the state, and those who do not. Those who control the means of coercion had the opportunity to reorganize productive relations through dispossession of the colonized Oromos in order to expedite more product extraction.

The process of dispossession is multi-faceted and far-reaching. As the result of it, the Oromos have been denied power and access to education, cultural, economic and political fields while at the extremes, the Abyssinian colonialism has been practiced through violence, mass killings, mutilations, cultural destruction, enslavement and property confiscation.

Apart from the splendid crop farm and animal husbandry, in his 1896-1898 travels in Oromia Bulatovich (2000, pp 60-61) described the Oromian industrial and commercial economy as the most vibrant with conducive endogenous institution as follows:

“Artisans such as blacksmiths and weavers are found among the [Oromo]. Blacksmiths forge knives and spears from iron, which is mined in the country. Weavers weave rough shammas from local cotton. The loom is set up very simple. … There is also the production of earthenware from unbaked clay. Craftsmen who make excellent morocco; harness makers who make the most intricate riding gear’ artisan who make shields; weavers of straw hats (all [Oromo] know how to weave parasols and baskets), aromers who make steel sabers; weavers who weave delicate shammas, etc.

Bulatovich Observed that commerce in Oromo was both barter and monetary based. The monetary unit was the Austrian taller and salt. The former was rather little in quantity and was concentrated in the hands of merchants. He witnessed that Oromos have great love for commerce and exchange economy. According to Bulatovich (2000, pp, 61-63):

“In each little area there is at least one market place, where they gather once a week, and there is hardly an area which is relatively larger and populated which does not have marketplace strewn throughout. Usually the marketplace is a clearing near a big road in the centre of [Oromo] settlements…. Rarely does any [Oromo] man or women skip market day. They come, even with empty arms or with a handful of barely or peas, with a few coffee beans or little bundles of cotton, in order to chat, to hear news, to visit with neighbours and to smoke a pipe in their company. But besides, this petty bargaining, the main commerce of the country is in the hands of the [Oromo], and they retain it despite the rivalry of the Abyssinians. Almost all the merchants are Mohammedan. They export coffee, gold, musk, ivory, and leather; and they import salt, paper materials, and small manufactured articles. They are very enterprising and have commercial relations with the Sudan, Kaffa, and the Negro tribes.”

The Oromos have also valued both the collective and personal independence and freedom very much. Their peaceful and independent way of life was broken and their freedom lost with the coming of the utterly vicious and sever authority and hard school of surrender and obedience of the Abyssinian conquerors. As Bulatovich (2000, p.65) further described:

“The main character of trait of the [Oromo] is love of complete independence and freedom. Having settled on any piece of land, having built him a hut, the [Oromo] does not want to acknowledge the authority of anyone, except his personal will. Their former government system was the embodiment of this basic trait of their character- a great number of small independent states with figurehead kings or with a republican form of government. Side with such independence, the [Oromo] has preserved a great respect for the head of the family, for the elders of the tribe, and for customs, but only insofar as it does not restrain him too much.”

Jalata (1993) sees the Ethiopian colonial domination as the negation of the historical process of structural and technological transformation. This is the case where the Abyssinian colonial class occupies an intermediate status in the global political economy serving its own interest and that of imperialists. The Oromos have been targeted to provide raw materials for local and foreign markets. Inside the empire, wherever they go, the Abyssinian colonial settlers built garrison towns as their political centres for practicing colonial domination through the monopoly of the means of compulsion and wealth extraction.

The Abyssinian colonial system was more cognated to a tributary system whereby the rulers extract tribute and labour from colonized lands. The Abyssinian peasants supported their households, the state and the church from what they produced. After its colonial expansion, Abyssinians maintained their tributary nature and established colonial political economy in Oromia and in the Southern nations. Although the colonial state intensified land expropriation and produce extraction from colonized peoples, capitalist productive relations did not emerge. Gradually with the further integration of the Ethiopian empire into the capitalist world economy, semi-capitalist farms seemed to emerge by extracting their fruits mainly through tenancy, sharecropping and the use of forced-labour systems.

The colonial exploitation has been maintained under Mengistu’s so-called socialist collectivisation/ villegisation campaigns and in the current Meles’ regime under the mask of structural adjustment and ‘free’ market economic system.

It should also mentioned that in addition to authoritarian and coercive rule, the Ethiopian colonialism depended on an Oromo collaborationist agents that were essential to enforce Ethiopian colonialism. This second rate clique is merely an expandable appendage which devotes most of its energy to the scramble for the spoils of slavery, picking up the leftover in economic and political advantages. The main task of this class is to ensure the continuous supply of products and labour for the settlers. Of course this class was not always loyal to the Ethiopian colonial state (Jalata, 1993). Broadly speaking, the state itself is a battlefield for two exclusive claims to rule and political competition among the Ethiopian colonizers, the Amharas and Tigreans. In effect, this makes the Abyssinian colonizer politics effectively a zero-sum game and the very practice of politics become a negation of politics, i.e. politics are practiced with the inert ending of politics.

The Abyssinian rulers, who have inherited power used to believe that their interests were well served by depoliticising, muting and suppressing the Oromos and the Southern peoples’ quest for national-self determination under the guise of maintaining the unity of the Ethiopian empire. So they convinced themselves and tried to convince others that there were no serious socio-political differences and no basis for political opposition. Apoliticism has been elevated to the level of ideology while the political structures become ever more monolithic and authoritarian.

The political structures and political ideologies, which have been used to effect depoliticization and suppression, are all too familiar. The process entailed political repression, which the Oromos endured and suffered for more than a century. The implication of depoliticization is to deny the existence of differences, to disallow their legitimate expression and, therefore, to deny collective negotiation. Whatever the degree of repression, the process did not remove the differences. The ensuing popular frustration and resistance has led to even more repression. That is how political repression has become the most characteristic feature of the colonial political life and domination as its salient political relationship. All this means that political power becomes particularly important; so the struggle for it gets singularly intense.